ICH & IK

A collaboration between Raum mit Licht and Geukens & De Vil gallery, Belgium.

Photo © Kunstdokumentation

Photo © Kunstdokumentation

Photo © Kunstdokumentation

The title of the exhibition Ik & Ich reminds us of Ole & Axel – those two friends whose souls were already imagined by the Enlightenment philosopher Jean Paul (1763-1825). They could not be more different and yet they follow the same path: irony is their leisure and the theme tune of their actions. With an unbiased view, they explore the everyday life of the bourgeoisie. We recognise the whole Conditio Humana in what they address and present to us. Finding and transforming things is an artistic strategy that surrealism eventually perfected. The Meret Oppenheimer’s „Luncheon in Fur „(1936) has become her signature.

We invited Peter De Meyer and Roman Pfeffer to an interview, and we have printed parts of it here.

RML: Can you remember the “innocent” first moment when you were so fascinated by a “thing” that you wanted to develop it into an artwork?

Roman Pfeffer: Eines der ersten Objekte, das von mir in den Kanal der Kunst hineingeschickt worden ist, war die Brockhausausgabe im Jahre 2006. Der Brockhaus, der das westliche Wissen, vor der digitalen Veränderung, für uns gespeichert hatte. Er wurde in die Ursprungsmaterialität zerlegt – in Papier und Farbe, also neu geordnet. Somit befindet sich der Brockhaus am Nullpunkt und es ist wieder Speicherplatz für Neues vorhanden. Die Rückführung auf die Ausgangsmaterialien beschäftigt sich mit der Frage „das Ding“ neu zu denken. Titel der Arbeit war „Wissenswertes über das Wissen der Welt“. Die 30-bändige Ausgabe des Brockhaus 2006 war der Ausgangspunkt. Entstanden ist eine vom Originalformat ausgehende Papiersteele mit einer Höhe von 132 x 24 x 17cm, die obenauf die Schichten der Druckerfarben (yellow, magenta, blue und black) hat. Die Druckerfarbe und das Papier haben das Potential, Inhalte zu fixieren.

Peter de Meyer: At a young age I looked at things around me a bit differently and I started to interpret them in music, crafts and drawings. There was always a big dose of fantasy involved. In higher education, I studied Interior Design and Furniture Design. During this last training I often flirted with the boundary between design and art. For example, I made a piece of furniture that you cannot sit on: functionless design. From there I evolved further towards visual art. One of the first works I came out with is down. In this work, I bring to life a robust, static object – known as ‘the buck’ from gymnastics class – through a subtle intervention: I laid the archetypical gymnastics equipment on its side and reassembled the legs so that it becomes a defenceless and vulnerable animal and introduces the idea of loneliness and transience. Functionality has been completely omitted. The abstraction of functionality is also very clear in a work like a sculpture a day shown in this exposition. At first glance, it’s just a white tissue box. The idea behind it is that every time someone takes out a tissue, a new and personal sculpture emerges. The work also refers to the fact that art can move people and to the different interpretations of art.

RML: Are you currently looking systematically for things with “potential”?

Roman Pfeffer: Selten suche ich nach Dingen. Wenn mich eine Form/Oberfläche oder das Design interessiert, kann es sein, dass ich diese Objekte/Materialien sammle. Mit der Zeit entwickelt sich daraus ein Werk. Es kann auch sein, dass auf dieses Werk weitere folgen und am Ende das Ausgangsobjekt nur noch in der Verweiskette eine Rolle spielt, aber nicht mehr als Objekt an sich.

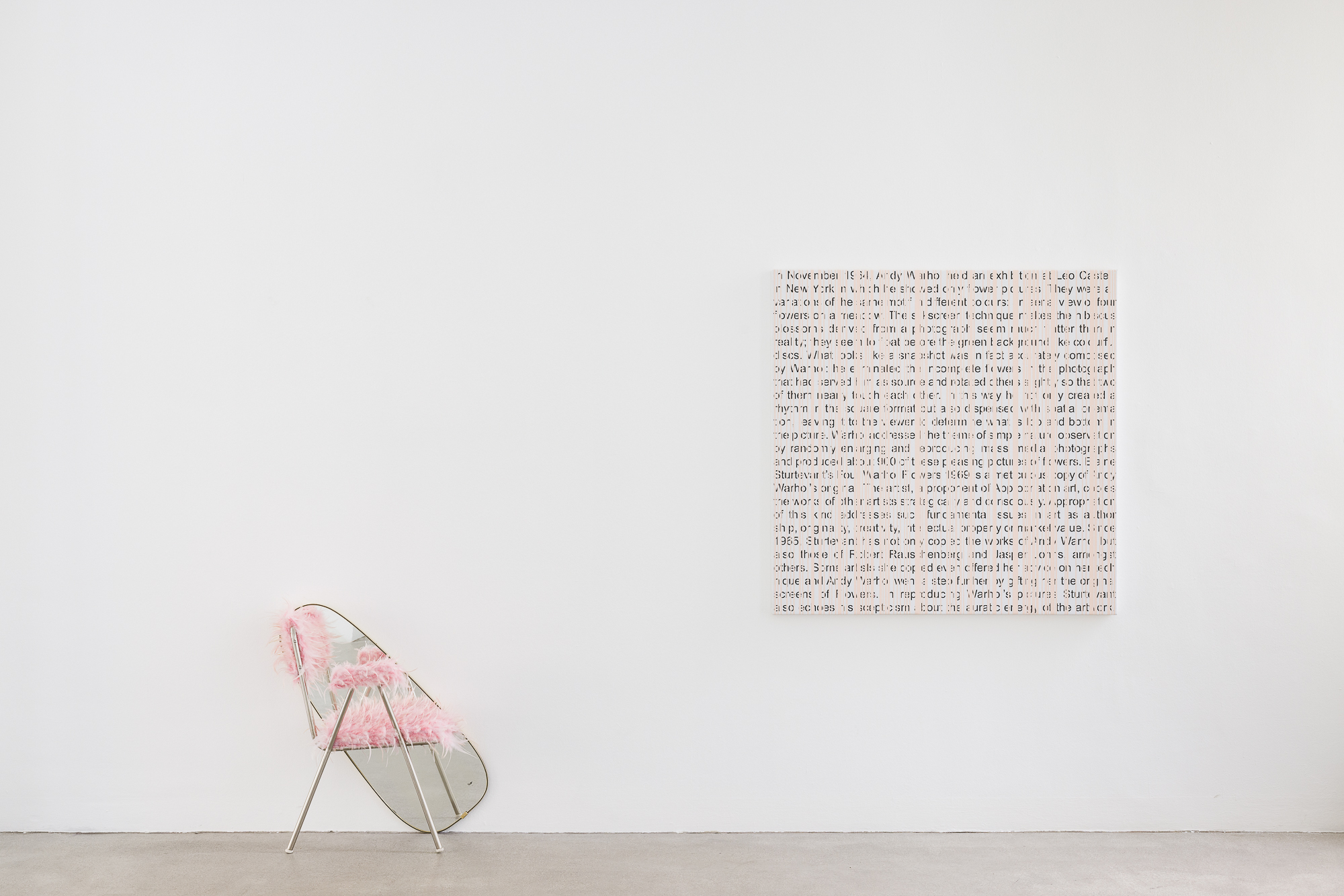

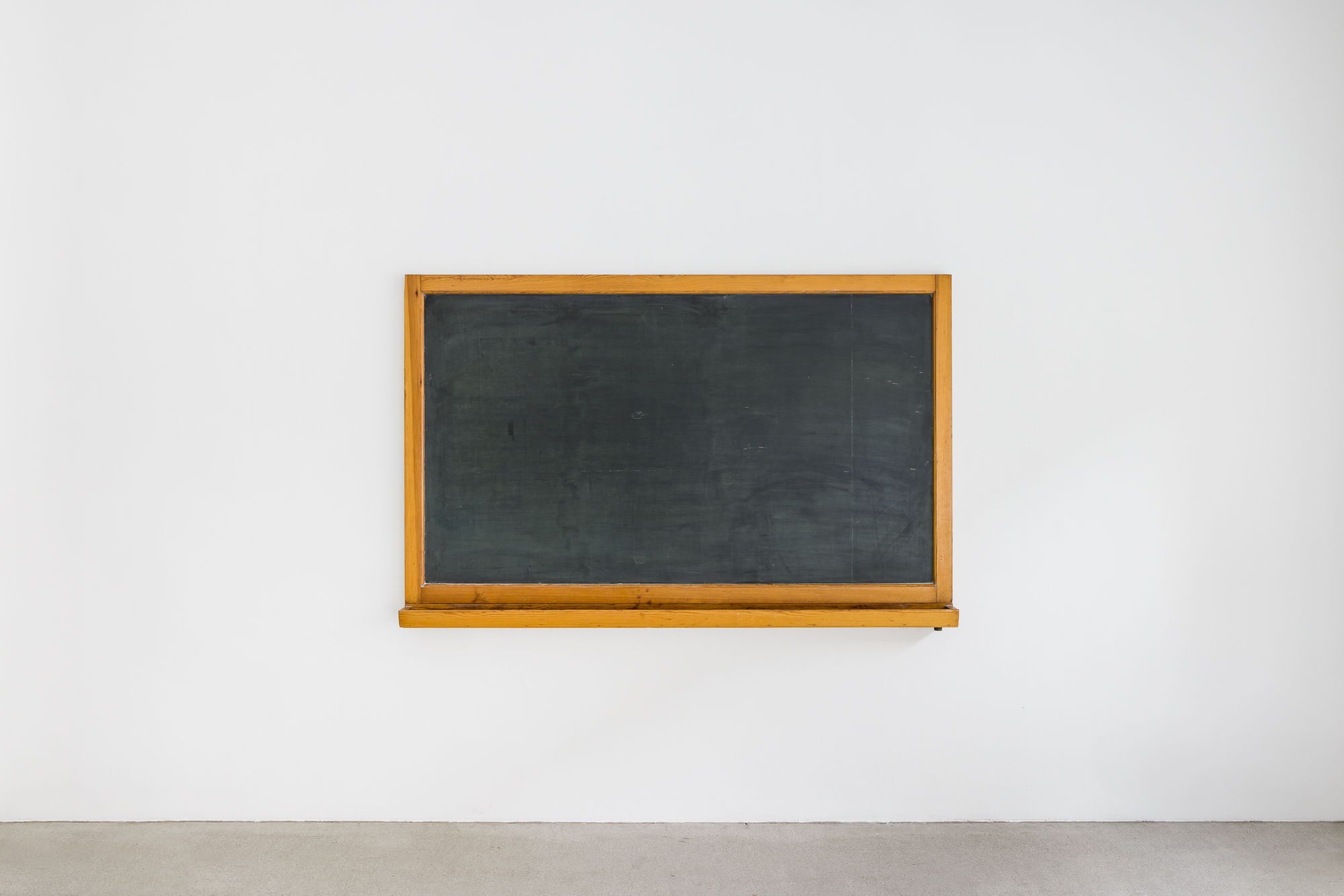

Peter de Meyer: I will definitely look for things with ‘potential’. What is important to me is that the objects I use are recognizable. This has to do with the fact that in my work I investigate the process of observation and perception by shifting context and meaning. I often start from the idea that objects, both in the individual and in the collective memory, are anchored in associations. Using subtle interventions and creations, I want to break through certain patterns of expectation and create the conditions for making the invisible visible. For this I build, as it were, on the metaphorical meaning of an object. Examples of this are hooked and the blackboard. hooked is a fishing rod, attached to the ceiling of the gallery. It represents the strong connection between the gallerists and the artists, the fact that they are hooked to each other by means of a thread such as that of the Fates. For the visitors, the question remains: who caught whom? the blackboard is a black school board. Since the chalks have been replaced by pills, the big black board can be interpreted as a reference to both an empty sheet and the infinite. The pill-chalks are there to symbolize how individuals often cope with emptiness in all its meanings.

Important to add is that I no longer limit myself in my creation process to mere objects. In the past, my work always started from an object in my immediate environment, and I tried to add a new context to it. This usually happened quite quickly and intuitively. Now I often start from a certain idea and look for a way to express it. I also find that I now put more emphasis on the process. This is undoubtedly related to the fact that I stay closer to myself, do more introspection, have more eye for the world around me. An interesting work in this regard is the curve, a series of 9 leather belts with a hole at different levels. It can be seen as a graphic that shows the inequality between individuals by means of the different waist circumferences. The holes so reveal where individuals find themselves in the world or in their lives.

RML: How would you describe a prototypical finding process?

Roman Pfeffer:Alle Objekte haben eine gewisse Senderfunktion. Ich denke, es ist eher das seismographische Ausschlagen einer unbewussten Kompassnadel, die den Ausschlag gibt, ob ein Objekt des Alltags zum Kunstwerk entwickelt wird. Ich wähle Dinge aus, die an sich schon eine gewisse subjektive Qualität für mich haben. Der Stuhl, den ich für den „Permanent Selfie“ ausgewählt habe, hat an sich schon einen Charakter, der für mich interessant ist.

Peter de Meyer: I used to look for objects that I would collect somewhere in my studio. I soon realized that in this way I was dragging the whole world into my studio. I was the hamster artist or is it an art hamster who kept track of everything because it could serve as inspiration at some point. In the meantime, my studio orientation has made way for a broader global base without a collecting rage. I take long walks, talk to people, listen to music, and visit exhibitions, thrift shops and flea markets.

In addition to the collection of objects in my studio, I have a large digital archive with Photoshop sketches of ideas and of objects for which I have already thought of a possible transformation. The realization of an exhibition often starts with browsing through that archive. Besides, a particular theme or, in this case, a dialogue with another artist makes me recapture a certain object, look for a specific object or create something completely new. A good example of this is self-portrait. After seeing Roman’s The artist in a made-to-measure suit, a self-portrait with exactly his length and volume, I chose to combine a static ready-made pole with my length and a playful party hat, both to tackle the idea of categorization – of artists and people in general – as to put myself into perspective – as an artist and a human being.

Of all the objects and sketches in my possession, some will be worked out for an exhibition, while others will be archived or disappear for good. For my exhibition heads and tails (2017) I made a work about this: in memory of. It is a marble memorial plaque with the text: In memory of the works of art that did not make it into the show.

RML: Can you tell us a bit more about how a dialogue can develop between you and the things you find?

Roman Pfeffer: So einfach ist das nicht zu erklären. Es gibt Werke, bei denen der Ursprung der Dinge gut sichtbar ist und dann gibt es welche, die nur noch daran erinnern. In der Ausstellung werden zum Beispiel Arbeiten sein, deren Ursprung Schrift ist. Buchstaben haben eine gewisse Form und Oberfläche und durch die Aneinanderreihung der Buchstaben entsteht Inhalt. Das ist eine Methode, die meiner Arbeitsweise nicht untypisch ist. Es ist ein Zusammenspiel von mehreren Faktoren nötig, damit ein Objekt oder eine Form zum Werk wird. Die Textarbeit „IK“, die aus 20 drehbaren Platten besteht, ist im Ursprung nur ein Schriftzug, der ins Deutsche übersetzt ICH bedeutet. Verwendet werden Buchstaben, die uns vertraut sind. Durch die Zerlegung in 20 Teile und dadurch, dass jede zweite Platte nach links gedreht ist, entsteht ein abstraktes Bild. Schrift ist Ausgangspunkt, aber durch den Eingriff wird die Schrift etwas Anderes. Ist es Text oder Malerei, ist der Inhalt des Textes noch wichtig oder reicht uns die Komposition? Das Wissen, dass hier ein ICH zerlegt wurde, könnte schon eine Rolle spielen. Möglich wäre, die einzelnen Platten zurückdrehen, damit alles wieder in Ordnung ist. Was noch dazu kommt ist die kulturelle Komponente, da das IK kein deutsches Wort ist, also übersetzt werden muss. Und das ist eine weitere Abstraktion. Und Abstraktion spielt eine große Rolle in meiner Arbeit mit den Gegenständen. Am Ende ist meist ein abstraktes Werk vorhanden, das eine Referenz an Materialien und Objekten hat, die uns eigentlich vertraut sind. In der Abstraktion gibt es Potential für Interpretation und das Absolute wird ausgehebelt.

Peter de Meyer: In the dialogue between myself and my objects or ideas, a few themes come to the fore. In the first place, I reflect on the meaning of art by thinking not only about the art world itself, but also about my position as an artist. I am thinking of hooked mentioned earlier, but also of one of my other self-portraits, a picture of myself completely covered in thumbtacks. The work is about the fact that I prefer to put my work in the spotlight and not myself. Navel gazer can also be added to this list. It is a stretched canvas in leather with a button in the middle, inspired by the Chesterfield or other sofas I was confronted with during my training at university college. In the first place, the work refers to the idiom used to describe a narcissist, someone who is absorbed in his own thoughts, feelings and concerns, to the exclusion of all others, as a person staring at his own belly button. Secondly, the work visualises the idea of the public looking at the artists looking at themselves.

A second theme in my work is the creation process itself. In 2017 I devoted an entire exhibition to this theme: heads and tails. Another example of this is the work coda, which is now part of the collection of museum Voorlinden in the Netherlands. As a kind of sculptural landscape made up of a large number of glass jars that were used by painters to wet and rinse their brushes, it refers to shifting the end point of the expected result to the process: the waste that is normally neglected as a residual product of the result is elevated to a sculpture.

The last theme that comes up regularly, is the reflection on the individual himself. For example, it can be found in point of view, based on a dental mirror. Through the small surface, the person looking into the mirror only sees a detail of himself. The underlying meaning is that people often tend to lose sight of the bigger picture, their surroundings. My arrow and a lifetime are also illustrations of this theme. My arrow, two merged arrows pointing towards each other, represents the inner tension, the inner conflict. The fact that the arrows are pointing towards each other can be seen as a pointless action, since the outer target will never be reached. As a key box in which 99 identical candles are hung from their wick, a lifetime is about transience, about the temporality of a human life and the fact that no one can control it.

What I find is that my play with perception often gives rise to seemingly contradictory interpretations: from a tragic view on things to a smile. Of course, a wink and cerebrality are not necessarily diametrically opposed: a smile does not equate to banality or mere gimmick, while cerebrality does not have to exclude humour.

Thank you very much for the interview!

[The interview was conducted by Heidrun Rosenberg]