CRISSCROSS

»Crisscross« features recent artwork by Käthe Hager von Strobele and Eva Stenram, two artists whose explorations go beyond an interest in the materials and textures of domesticity. As the show’s title suggests, »Crisscross« highlights a palpable back-and-forth dialogue between the works of the artists, who share a common interest in employing the tools of interference. Reminiscent of interference in the natural sciences that describes the phenomena resulting from interaction between waves or biological processes, interference in Stenram’s and Hager von Strobele’s works likewise operates as a catalyst in their artistic production.

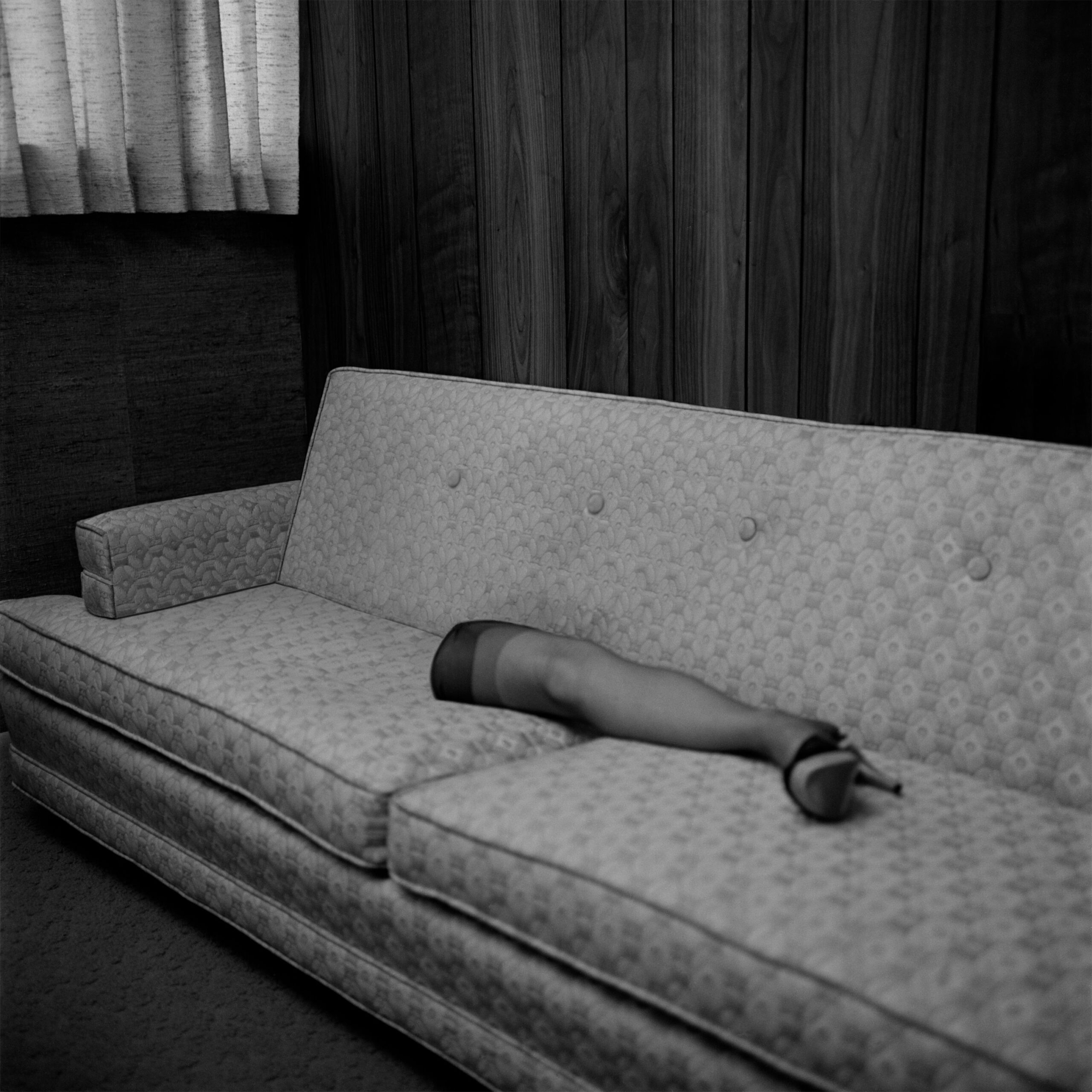

Eva Stenram’s sources are the pin-up photographs of women in almost exclusively domestic settings from the 1960s. In the series Parts (2013-2014), disembodied stockinged legs seem arbitrarily cast off onto generic beds, boxy sofas, and densely carpeted floors. The artist has digitally manipulated found magazine photographs and replaced the remainder of the woman’s body with the very fabric of its surrounding interior décor. The now somewhat macabre scenes have minimized the originally intended erotic content, shifting the focus of desire from the body to the cushion as the ersatz for pleasure.

In Drape (2011-2014) the background curtains in the erotic images have been duplicated and used to obscure the women in pose, all the while unveiling their limbs and suggestive gestures. In an ambiguous gesture that may be read as once again eroticizing or objectifying the woman’s body, attention is simultaneously drawn to the stereotypically inextricable place and role of the woman embedded within the home, domestic space inscribed upon her body. The interruption of the source material is formally reinforced in a couple smaller works that include white space around the manipulated image, an area that was originally filled with magazine text. This space is not unlike the invisible space between the artificially introduced veil and the woman’s body, allowing the viewer to imagine, in Stenram’s own words, a “possible slippage of the woman into a new space.”

For her textile piece, Daydreams are nicer than T.V. (2015), the artist has recreated the recurring floral pattern of a bedspread by digitally printing it onto fabric for use as cushion covers. Here, the settings of the photographic pin-up fantasies are given “tactile form in real physical space” (Stenram), yet not as mere reproductions of the retro prop. Rather, especially manifest in her hanging piece Home-town item (2015), Stenram integrates the pattern’s very disturbances—the imaged wrinkles as well as the inherent attributes of photography, such as the flattening, foreshortening, and distortion of the pattern.

Patterns, textiles, and visual interferences are equally central to Käthe Hager von Strobele’s artistic practice. In Moiré (2015), the artist clothes lifeless dress forms with shirts in conventional checks, stripes, and polka dots upon which she has applied irritating moiré patterns. Other household items, also alluding to interference—a fan (air waves) or speakers (sound waves)—are included in these stagings. Rapport (2015), a series of photogrammes produced with analogue techniques using transparencies in the darkroom, further exemplifies the artist’s preoccupation with reproducing the moiré, an undesired effect that is slowly becoming obsolete in the digital world.

Hager von Strobele consistently addresses the notion of both textile and photography as the surface or skin upon which identity is projected. While the physical body is generally merely implied in her images and objects, specifically coded textures, textiles and settings allow the viewer to draw a conclusion about or construe a specific identity that might well inhabit the space within the glass cases she frequently uses to display her work. For example, in the haunting scenes of the series exterior/interior (2015), the artist couples mannequins in outfits featuring retro and outlandish patterns with isolated outdoor settings. The analogies between the featured textiles and surrounding architectonic structures is striking and demonstrates how the artist deliberately invokes the viewer’s preconceived notions about specific patterns and styles, inevitable calling them into question.

For Hager von Strobele, including traditional patterns in her vocabulary also means to rupture them. In a conflation of high and low culture, the artist has infused the original tacky floral pattern of fauteuils with high-end damask for the sculptural objects Bubble Chair (2015). The patches or extensions replace the fragments that the artist has removed from the armchair, retained to be both displayed and examined as relic, an archaeological artifact in a glass case.

In this vein, the use of the term “interference” in social sciences and psychology to explain memory and learning processes as the interplay between newly accumulated and already acquired knowledge and skills is of greater significance to Stenram’s and Hager von Strobele’s art. The artists achieve visual disturbances through overlapping or intersecting images, intentionally crossing wires and introducing errors or defects to the viewing process with the intent of distorting or creating new meaning. Both introduce crosstalk to a stock of familiar, often stereotypical images and patterns causing the viewer to pause and reflect not only about what is being seen, but more significantly, about how viewing takes place.

Text: Melissa Lumbroso (2015)