UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Imagined Spaces

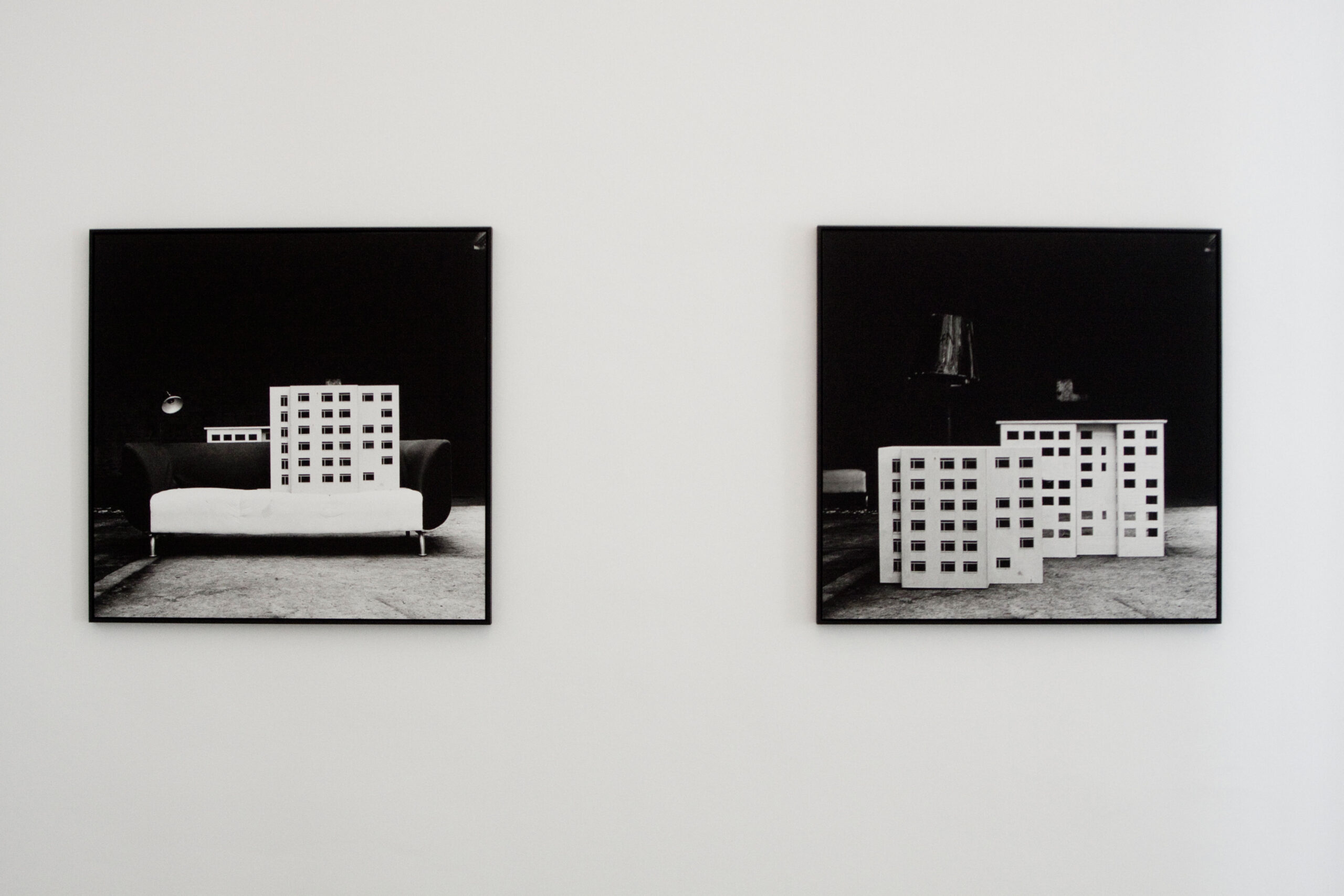

Ernst Koslitsch’s models invite a look into to secret worlds, into intimate spaces. The models instigate a reflection on perception and form associations on several levels, on plateaus corresponding to the multi-layeredness of the perception of space. Firstly, the poetics of the models, in the housing, furniture, apartments, and in the public surroundings of dwelling places are brought to light. A second poetic level is that of the photographic image, which is more than a representation of the model yielding its own reality of a modeled and an imagined space.

The models of the living quarters show conditio humana: things that account for the human condition. Not only the objects of dwelling, of living and of play, but also the house and the apartment itself are things. We dwell in such things, we are inhabited by these things, our order is determined by them. People make their own history, “but they do not make it as they please” (Karl Marx). And the models of things point out that things form our lives, to put it more bluntly, things make us humans. The form and function of apartments and houses dictate the context in which we move and operate, in which we live and deal with each other. We function according to the function of these things. The exterior and the interior, the floor plan of the bedroom, living room, kitchen organize our lives into different worlds, into public, partially public and intimate, private spaces. Even in the private and intimate worlds, we appear to lead a standardized life, a life according to a model. The models allow a look from the outside into the interior space through a hole where a wall is missing, through an oversized window. They take the privacy of dwelling and fulfill what Vilém Flusser announced with his ideas about the nomadic human of postmodernism: “The perfect house with a roof, walls, windows, and doors exists only in fairy tales.”1 Or, elsewhere and with greater clarity, Koslitsch illustrates the already completed demolition of domestic privacy, the rear wall of the house is missing: “The perfect house has become a ruin through whose cracks gust the winds of communication.”2

The interiors of dwellings are turned inside out. Not only is the architectonic bearer of form, the outer wall, public and thereby political, even the interior wall becomes visible and allows access to the curious eye of media. The model simultaneously reveals and alienates: It takes what is foreign from the interior spaces and turns it into a projection space of fantasies and perversions.

The invasion of media communication becomes evident in the photographed model: “The home has become drafty, as gales of media sweep through from all directions […]”.3 The model is a poetic space, closely connected to the television. Ernst Koslitsch explores this phenomenon of television infiltrating private life, of soap operas and telenovelas generating their own realities and providing templates for our lives in houses and apartments.

Koslitsch guides our view into the models, into the private life that we both assume and imagine goes on behind the walls. The media construction allows a turn in the direction of perception. The tables are turned: The world is no longer observed safely from the interior of the home through a window, rather the world within is seen from the exterior, a peep show of imagined intimacies, a variety of projections of personal longings and fantasies in this inner world. The models allow a public view of human intimacy – like a reality show on television.

The photographic view stages the model once again – and in fact, on different level. The photograph documents that which is constructed. It is a fictitious representation of a fictitious reality, and as a result, turns it precisely into a non-fictitious reality. The photograph functions by allowing the perception various associative and imaginative approaches to the model, and the model is shifted even deeper into the imagination of the viewer. Koslitsch thus becomes the magician of images: the double imago (imagoalso contains roots for the word magic), the double media refraction of reality, first in the model, then in the photograph of the model, forcing an emotional confrontation with the social reality of space. Is it the irritation of that which is doubly “constructed” that sheds light on our projections and fantasies? Or is it the emotional effect of the newly created realities when one looks things from “around the corner”, which, according to Nietzsche, is something we “should learn from artists”?4 We see not only that which we want to see, rather the view imposes itself on us, it affects us in return. It takes possession of our thinking and our pattern of perception that is still operative, even when we do not want to see and we attempt to withdraw ourselves from that which encroaches upon us. The image and its atmosphere affect us: The more they run into obstacles, the more they are charged with emotion.

Our pattern of perception that is revealed to us with the photographs, but also with the models themselves, is individually, subjectively shaped by the experiences had in each individual living space referenced in the models and photographs. To an ever-increasing extent, this pattern of perception evolves through images, through spaces communicated in the media that are often indistinguishable in one’s own reflection. (Does looking at a building remind us of a building we once lived in, or does it remind us of looking at a photograph of exactly this building?)

In addition to the individual perception there is the collective, cultural pattern of perception, which is increasingly communicated by the media: the collective memory of a postmodern society. It is no longer the common experiences with “the stones of the city”,5 with houses and monuments that we recall together when we speak of a certain city. The fountains of Rome as well as the Plattenbauten of the Petrzalka district in Bratislava are memorized images; indistinguishable from experienced reality, they are part of our common, collective visual world. And hence the images that we remember, that we have “stored”, precede perception.

Koslitsch points this common pattern of perception out to us, he points to the images that we share and to the emotions in us that can collectively be mobilized. How much do we think along the same lines after all, when models and photos of models trigger the same emotions in us – collective emotions?

Ernst Koslitsch has created modern stage sets with his models. While the maquette – a scale model for stage sets in theater and opera – presents the stage play, Koslitsch’s models are maquettes for the drama of (post)modern life. We experience ourselves on these stages. In fact, we are ourselves going about our lives in these models: “Our Town”, Ernst Koslitsch as “Stage Manager”. Is not the gallery, where the models and photographs are exhibited, itself the stage upon which art is staged? And in fact, “more real” – because in the everyday life of our own living spaces, in the city, in houses and in apartments, to be present does not always mean that we are also there with our perception, rather our perception is consumed by the ubiquitous images of the media that are in and around us, on-site.

The city is no longer the ensemble of collectively remembered stones, as Halbwachs postulated almost one hundred years ago in his theory of collective memory, at a time when photography and film were still in their infancy. Instead, the city is today a spectacle of images.

The models of the city and its buildings refer to an experienced space, crowded in the background with photographs and films, a million fold, ubiquitous in our perception. Films from the beginning of postmodernism make the spectacle of images their central theme, like Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point. The house explodes without sound, items from the house, furniture, objects of everyday life are flung into the air, all to the music of Pink Floyd. These are images that allow reality to explode.

Themroc, a film directed by Claude Faraldo in the early 70s in the banlieues of Paris, thematizes a revolt due to a break with standardized way of living. The protagonist breaks out of the predetermined structure of everyday life, throws furniture out of the window and builds a wall sealing his apartment off from the balcony. He creates a cave, a new unregulated space facing outside. In this space, he leads an archaic and anarchic life, exposing the viewer to the effect of shocking images.

Ernst Koslitsch’s images, models and photographs are less shocking at first glance. Yet giving in to the emotions of the “ver-rückte”6 spaces, for example a house on a kitchen table, entails a radical rethinking of our living spaces. We are confronted with the visual constructions of our spatial reality and with the question: “How do we live in a world where images precede reality?”

Gerhard Strohmeier 2009

1 Vilém Flusser, The freedom of the migrant: objections to nationalism, Illinois, 2003, pg. 57.

2 Ibid., pg. 57.

3 Ibid., pg. 42.

4 Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science, Cambridge, 2001, pp. 169-170: “To distance oneself from things until there is much in them that one no longer sees and much that the eye must add in order to see them at all, or to see things around the corner and as if they were cut out and extracted from their context, or to place them so that each partially distorts the view one has of the others and allows only perspectival glimpses, […] all this we should learn from artists.”

5 Maurice Halbwachs, On Collective Memory, Chicago, 1992.

6 A play on words, with “ver-rückt” meaning both “insane” and “displaced”.